- Home

- Corballis, Tim

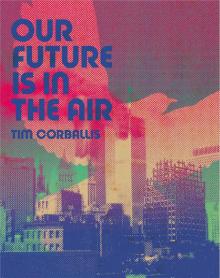

Our Future is in the Air

Our Future is in the Air Read online

VICTORIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Victoria University of Wellington

PO Box 600 Wellington

vup.victoria.ac.nz

Copyright © Tim Corballis 2017

First published 2017

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the permission of the publishers

ISBN 978-1-77656-117-9 (print)

ISBN 978-1-77656-136-0 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-77656-137-7 (Kindle)

A catalogue record is available at the National Library of New Zealand

Published with the support of a grant from

Ebook conversion 2017 by meBooks

CONTENTS

Front Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Happy are those ages when the starry sky is the map of all possible paths—ages whose paths are illuminated by the light of the stars.

—György Lúkacs

Time-painting has abandoned the indeterminacy of words and now possesses an exact unit of measurement.

—Velimir Khlebnikov

CHAPTER ONE

‘At first the future seemed like this: black, but with a smattering of stars. It was a mystery to us, this photograph. We did not yet have any idea that it showed the future. It came from the bubble chamber of the Laboratory’s accelerator and showed points of white in place of the usual linear trails, as if one of the cameras had recorded stationary objects instead of fast-moving subatomic particles. At first we had trouble reproducing the result—it was, we thought, the outcome of some error in the machine’s operation or in the development of the photo. EM, however, went home and, by his account, stayed up all night for three nights running, trying to work through the initial conditions that might have led to the unusual result. He never explained his thinking or his intuition that the image was not just a freak accident, but his workings from those days are now famous in the community of high-energy physicists. When he returned we set about putting the new experiment in motion, and, sure enough, we were finally successful: another photo, much like the first, in fact showing almost if not exactly the same constellation of white points. The outcome was subsequently reproduced many times. It was always from just one of the bubble chamber cameras, the others showing the usual particle trails and collisions. What was strangest was the sense we all had of SEEING SOMETHING. Normally, in our results, we knew that we were only witnessing traces or results of the various particles unleashed by the synchrotron, say, as they passed through the chamber’s near-boiling hydrogen—that we could never look straight at the particles themselves. We all confessed to one another at some point that the normal inaccessibility of our objects of study gave us a sweet and sorrowful feeling. We generally felt more of a physical excitement when faced with the great machine itself, heard its noises, stood in the circular building that housed it, or even outside in the California sun and noted that the building’s curved walls marked out the curve followed by the particle beam inside. The solidity of all this was comforting, and contrasted with the sketchy results—however repeatable they were—recorded in the photographs. This new photograph, however, was something different, as if we were looking through it, straight at a night sky. Of course it would later prove that, in a sense, we were.

‘When we asked EM about the calculations he had made on those first few nights, and about what theoretical vision lay behind them, he didn’t answer us. Instead, he talked in quite unusual ways. We were all familiar with the manner in which pictures could grip the imagination—battlefield photographs of the First World War, photographs of the Nazi atrocities. There were Germans among us. But, more importantly, many of us had been involved with the Manhattan Project, and had, since then, from time to time turned our thoughts to the images emerging from it: explosions and mushroom clouds—which many of us had experienced at first hand—as well as the scenes of obliteration and devastation that our work had wrought in Japan. We were very sensitive to pictures, to those powerful pictures, since we had in a way helped to produce them. Technology had, moreover, given us more and more perspectives at the same time as it gave us more and more powerful forces and tragic events to focus those perspectives on: views from the front line, from the air, and even from outside of Earth’s atmosphere. This was only a short time before the famous view of Earth from the Apollo 11 mission was published—a perspective undreamed of, and which showed our planet small, fragile and isolated, a moon of its moon. EM was convinced—how could he have known?—that our strange experimental result would provide another one of those famous pictures. Certainly our photo held a kind of power over him. He talked about photographs and pictures, and held a print of one of our exposures in his hand as he did so. He talked about the view that the photograph gave us. He seemed certain, more certain than any of the rest of us, that it was a view, or rather a perspective. He told us again—of course we knew—that he had taken the initial print home with him when he had done his calculations. He told us that he had looked at it over and over again. What were we looking at? We had all dreamed, in different ways, that our work might one day lead to an ENCOUNTER of some kind with the most fundamental forces of the universe. Not a few of us held Christian beliefs. Were we looking deep into something significant? Did this picture have something to do with the obscure, impossible encounter we had dreamed of? EM was sure that it wasn’t anything of the sort. He was perhaps the most hard-headed, the most atheistic of us. Normally this didn’t affect his demeanour in any way—in fact, he was usually quite cheerful. Even now he wasn’t unhappy in any obvious way, but rather manic and overwrought in ways that frightened some of the more timid doctoral students. He said he had been having conversations with a university astrophysicist, who had given him the opinion that, almost impossibly, the view we had in the bubble chamber photograph might in fact be a view of heavenly bodies—real objects in space. The astrophysicist had said that some of the white points had the distinctive oval shape of distant galaxies, while some had the “round” appearance of stars. It looked very much like a view out, from somewhere near the edge of our own galaxy, a view not unlike that of parts of our night sky, but without being identifiable as any particular section of it. This was presumably a mistake. EM however did not think it was a mistake. He was prepared to take it seriously. It meant not only that the photograph was a photograph of an unidentifiable set of objects, but that it had been taken from a point in space that was unidentifiable and presumably not on, or near, Earth’s surface. This in itself was astounding but we had to be open to the possibility.

‘EM was working on a theory to account for what he had started to call “lensing”, by which even the relatively low energy levels of our recent synchrotron experiments might allow electromagnetic radiation from some other point in space to be focused into the space of the bubble chamber and be recorded by the camera. A tremendous accident, he said. Had we accidentally discovered something like a telescope? More than that, since telescopes simply magnify a perspective that is already available—this allowed, he thought, a view from somewhere altogether different, a whole different perspective, a different “eye”. Except—and here’s the point—this eye is

no eye. It is likely to be, EM said to the rest of us, the truest picture ever taken. This cold view, this view of nothing much—of the gases of stars and nebulae, of great, distant and chaotic accumulations of the dumb particles we had given our lives to—was the perspective of an astronaut stranded without help; floating, impossibly far from anywhere. But more, there was no astronaut. Even the pathos of that story, that lonely astronaut, the sadness of the astronaut’s last breaths and desperation to be back home—that pathos was absent from the photograph. This was physics, said EM. This was the nature of the universe: particles and waves, radiation, interactions. This was why it was so shocking to him, and later also to many of us, when we understood that he was in some ways correct. Its shock was the shock of that photograph of Earth from the moon, but without Earth, without moon, without the recording eye or even the recording camera. It was a picture of pure, meaningless indifference. Put next to that photograph taken on the moon, it made Earth look like an arbitrary thing, something that might as easily not have been there. Somehow this view had landed on us, inside our machine, and was recorded by a camera intended to record the bubble trails of hydrogen boiling out of a liquid state upon interaction with subatomic particles. The light registered by the camera—if it was in fact the visible spectrum that was recorded, or rather the interaction of some other radiation with the emulsion surface or the liquid hydrogen—came, not from the direction of the synchrotron beam (since the cameras were not focused in that direction) but from another angle, as if it was simply coming from outside the machine, through its wall.

‘What could cause such lensing? The theoretical basis for it is recorded in all its detail elsewhere. Only a few people understand it fully. Here, however, we can note that EM was both right and wrong. Yes, this view did show actual stars and galaxies, and in a sense they were from another place. This in itself would have been a serious challenge to the fundamental theories, which held that nothing, no radiation or information, could travel faster than light. And in fact that rule was not broken in the final theory of lensing. The “lens” or “tunnel” (the theory described both terms approximately, but neither exactly) did not lead outside of the “light cone” of a point in space-time. Some have since argued that causality in the “lens” was reversed and compressed, but this is an awkward formulation since “causality” itself is not a term within our formulae. But the point was that the “lens” pointed nowhere that could not be travelled according to the understood laws of physics, given time. It was precisely the time taken, the “travel time” between here and there, that was obviated. What was brought together was not two simultaneous points in space, but two points in time. The lens, as we all now know, pointed at the future.

‘How far into the details of the process and the niceties of the Theory of Relativity is it necessary to go? Probably not far. The ultimate outcomes of the discovery of lensing are well enough known. But it should be said that between that initial discovery and the production of recognisable images of our own future, there was a great deal of work. We think the Soviets solved the basic problem before we did. Certainly they were instrumental in making public some of the first, most notorious and damaging photographs. But when we found that we had this small, unexpected window onto the future, there was a frenzy of activity. How could we turn this to meaningful use? It is hard to describe the atmosphere in our laboratory, or in the wider scientific community, during those early times.

‘The basic, theoretical problem was profound. What, after all, is the future of a place? What is “our” future? In the most fundamental terms, places have no physical existence. Earth—let alone any particular point on its surface—is from most larger perspectives a tiny rock, an object hurtling and spiralling through space, orbiting a sun that itself is moving at great speed. Earth itself, then, from the point of view of physicists, cannot really be said ever to stay in the same place, except from within a very peculiar and complex frame of reference. We are always leaving our place far behind, even as we seem not to move. Relativity’s most basic lesson, moreover, is that there is no singular frame of reference by which we might say that a place, or an object in it, is stationary at all. There is no reason our view into the future would show a place where our Earth might happen to be. This is why those first photographs show only emptiness; it is also why they continue to hold a profound or horrific fascination for many of us. They show the view from a place from which Earth, with all its life and humanity, its islands of meaning, has been and gone—it has been in this one place only for an instant, rushing past with all of its (to us) unthinkable momentum, accompanied by its whole whirling apparatus of sun, planets and debris. No god threw it—it had only the senseless energy of the universe behind it. EM might not have intuited the full nature of those photographs, but as we understood them further their significance for us deepened.

‘The solution to the problem, in practical terms, was technically complex but had its own elegance. In short, the lens or tunnel, the “path” from the present to the future, interacted with both gravitational and electromagnetic fields. Directed upwards with sufficient magnitude, it would leave Earth’s gravitational and ionospheric fields altogether and fly off to open in deepest space. Directed with lesser force, it would be captured by Earth’s gravity and ionosphere. Gravity would keep the tunnel following Earth’s own course, but only if its “throw” could be made stable through interaction with the ionosphere, effectively tethering it to a field line in a helical pattern. The gravitational-ionospheric interaction was inherently unstable, with a tendency to disintegrate chaotically on most initial inputs. However, a range of values was found that tethered the tunnel to a field line on a complex orbit that decayed back to the surface of Earth at the same rate as the tunnel itself degenerated.

Stability margins of TC-lens ionospheric field line tethering

‘Due to the constancy of Earth’s mass, rotational velocity and magnetic field, it was only possible to construct such a lens through to a time around thirty-three years in the future. It was possible, with minor adjustments to the lens intensity and angle, to take advantage of the helical pattern of field line tethering in order to adjust the point of opening on Earth’s surface by a few hundred miles—eventually, with some precision. Any further and the outcome would be wildly unstable and the lens would be likely to open, once more, far from Earth.

‘This was how we created the first link to the future.’

‘Dad.’

‘Shh. You’ll wake your sister.’

‘Dad. Can I see what I’m going to be when I’m older?’

‘Can you—’

‘Someone at school said—’

‘Honey, can you be quieter?’

‘Yes. They said at school that you can see yourself, you can visit yourself as a grown-up.’

‘Oh. Well, I guess—’

‘How can you?’

‘It’s sort of true.’

‘How?’

‘There’s a kind of machine. It’s interesting isn’t it?’

‘How does it work?’

‘Well… actually I don’t know. I think it’s very complicated. Do you like that idea?’

‘But how can you see yourself? If you are yourself.’

‘You can see yourself in the mirror, can’t you?’

(Breathing, the shuffling of sheets.)

‘Dad.’

‘Try to be quiet.’

‘Dad. I don’t understand how you can see yourself when you’re older.’

‘No. It’s a strange thing.’

‘Have you done it Dad? Have you seen yourself when you’re older?’

‘Nah. I’ve met some people who’ve done it. I haven’t seen one of the machines for a long time.’

‘Where are they? The machines.’

‘I don’t know.’

‘I bet they’re in America and Russia.’

‘Oh. Probably.’

‘Everything is in America or Russia.’

‘Yeah.�

��

‘There’s no machine here in Wellington.’

‘There probably is somewhere.’

‘Really?’

‘But you know, it’s not allowed. Maybe some scientists use them, but people like us aren’t allowed.’

‘Why not?’

‘I’m not sure. I think they think it’s dangerous to let people do it. It’s against the law.’

‘So we can’t.’

‘No.’

(A silence.)

‘If we’re scientists.’

‘Well, then maybe!’

(Silence.)

‘Can you sleep?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good. I want to go back to sleep, too.’

‘Okay.’

‘I love you.’

‘I love you, Dad. Dad?’

‘Yes?’

‘I want to be a scientist.’

‘That’s a good thing to be.’

‘If I was a scientist then I could meet myself in the future.’

‘Maybe you could.’

‘Bye, Dad.’

‘Goodnight.’

‘In 1968 the Soviets released a photograph from one of their own TCL facilities—it showed a human figure, blurred and difficult to make out, seemingly suspended against a pale sky. This was the first recognisably human image to come out of the TCL technology, and it was accompanied by the slogan THE ATOMISED HUMAN BEING OF A FUTURE CAPITALISM. One version of the Soviet THEORY OF TIME held, as far as we understand it, that it was still possible to change the future despite the photographic evidence of it—that no facts, even if they were apparently witnessed through TCL, were unalterable. The ATOMISED HUMAN thus showed only one possible future. Western physicists’ equations were incompatible with this result—for them, the images represented a kind of fate. It was clear, however, that the Soviets were unable to produce images of any alternative future—giving evidence of THE FAMILY OF NATIONS or THE PROLETARIAN IN A STATE OF OVERCOMING. Why had such futures faded?

Our Future is in the Air

Our Future is in the Air